History Lessons

Americans urgently need to crack open some history books

“It is sad but true,” the late Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough said in 1995, “that we are raising a generation of young Americans who are to a large degree historically illiterate.”

17 years later, as the youngest millennials trickled onto voting rolls, McCullough repeated the remark. Were he alive today, he’d no doubt still say the same. Given the lack of even rudimentary reading comprehension among today’s college students, he’d likely be even more critical.

While it may seem self-important for a historian to lament the declining appreciation for the art and scholarship he undertakes, in the recent posthumous collection History Matters, McCullough makes a clear case for why the study of history is so important.

”History shows us how to behave,” he wrote. “History teaches us, reinforces what we believe in, what we stand for, and what we ought to be willing to stand for.”

In America today we stumble amid a fog that future historians will spend generations peering through to reveal what led us down this lamentable path and why we failed to take the branching trails that regularly offered themselves to us.

Dissertations will be written on the 2024 election, the militarization of ICE, the disappearance of immigrants, the bombing of boats in the Caribbean, and the myriad other bits of concurrent mayhem occurring in America today.

And scholars will investigate just as thoroughly what everyday Americans did, or didn’t do, to oppose the nation’s first true authoritarian – as well as why we did, or didn’t do, what we did.

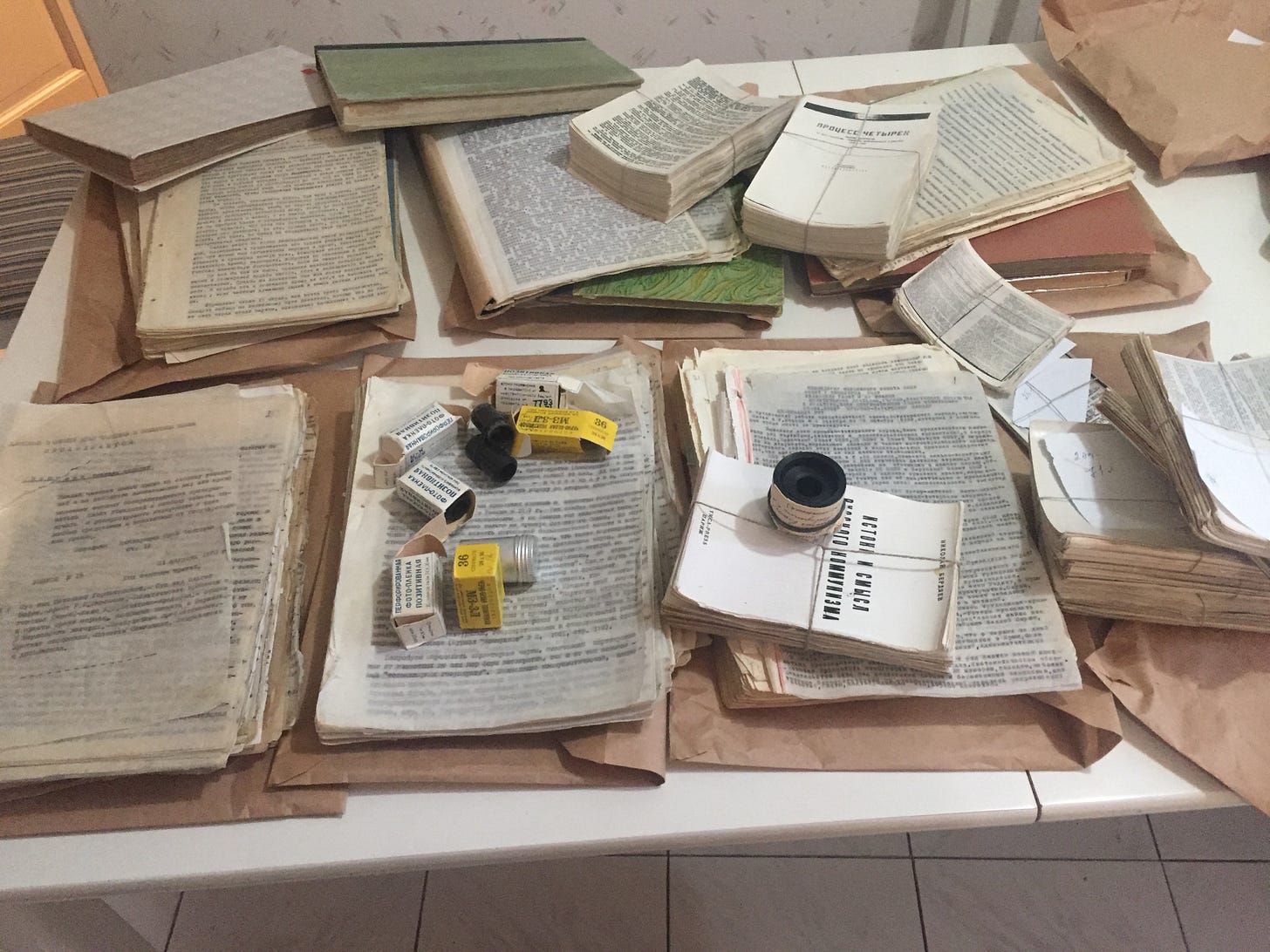

I feel confident that such research and writing will one day happen because I have, sitting stacked on my living room end table, a dozen books dedicated to underground resistance movements from generations past, including those that sought to counter slavery in the Americas, Jim Crow in the post-Reconstruction South, the Nazi takeover of Europe during World War II, and the Soviet repression of the USSR following the death of Stalin.

Though I have only just begun to read them in search of inspiration, the mere presence of these books reinforces another of McCullough’s insights: “Because we know what has been done in the past, we know what the standards are. We know what we must live up to.”

I’ve collected the aforementioned books because, as I see it, studying the successes and failures of dissident and resistance movements past and present is essential homework for resisting Trump and his administration.

We’ll have to learn our own lessons and refine our own best practices through trial and error, nonetheless. But understanding what worked (or didn’t) in the past can help shape our strategies today.

This practice of thinking and planning with a historical lens is, as McCullough pointed out and historian Francis Gavin emphasized in a recent column, a lost art. “Bad history, or no history,” Gavin said, “can lead to catastrophic policy choices.”

Although the challenges before us are not, primarily, those of policy, the lesson still applies: Poor history leads to poor strategy. The No Kings rallies evidenced this.

False Conceptions of Resistance

A cultural obsession with events like the 1963 March on Washington has infected a majority of Americans with an inability to imagine anything beyond the most impotent forms of nonviolent pseudo-resistance, and thus made mass gatherings and speech-punctuated parades the primary form of supposed protest we pursue.

To distill the Civil Rights movement into a single day demonstration misunderstands that period in our nation’s history.

That march was an exclamation point at the end of a decade-long argument composed of countless dependent and independent clauses linked, hooked, and spliced together through all the tricks of rhetoric available to the many grammarians that built the movement.

Without efforts like those to spell out the specific demands of an assembled mass, all that remains is a wordless shout.

Too often we get involved in a numbers game and forget that our goals is not to count ‘heads,’ but to involve those heads in meaningful action. But we get so involved in turning out large numbers that we forget about involving those numbers in anything significant.

These words of Julius Lester’s often rise to mind when I read news of protest. I’ve even quoted them in this newsletter before.

The gallup-poll, viral-moment mentality we display today is clearly nothing new. Lester wrote those lines in 1968 in a column for The Guardian.

But to continue in this pattern will prove fatal to the future of the American Republic. Only a proper, organized (if decentralized) resistance can save America. And while the fervent opposition to ICE that has erupted in Chicago, LA, New York, and other cities should be celebrated, that alone won’t be enough.

Imagining the Movement Anew

In a compelling editorial for The Atlantic, columnist David Brooks lays out a thorough, if unimaginative, argument for what a mass movement in America could look like and what it will take for such a movement to mount a meaningful challenge to Trumpism.

The essence of his argument revolves around identifying the weaknesses of the MAGA agenda, elaborating a more compelling and unifying vision, and, lastly, “actually build[ing] the movement and the vision.”

“Cultural and intellectual change comes first,” Brooks writes. “Social movements come second. Political change comes last.”

But Brooks—64-year-old moderate Republican that he is—has a decidedly lackluster idea for where the movement should seek inspiration. His chosen model is the Populist-Progressive coalition of 1880s America: a period infamous for the rise of the post-Reconstruction South that birthed Jim Crow.

Brooks’ vision for what a mass movements should strive for, then, is to return to the past, rather than orient ourselves around the specifics of our moment in all its horrors and all its opportunities—and the futures we must enact to combat the terrors and realize the possibilities.

We can, and must, learn from the past, but post-Civil War America wasn’t confronted with ascendant autocracy, making it a historical corollary of limited value. The resistance in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia is far more useful as our comparison, so too is the persistent struggle of Black people worldwide.

The title of Brooks’ essay is spot on: “America needs a mass movement, now.” But movements take time to grow and swell and achieve their greatest strength. If we prepared for the real possibility of a Trump victory back in 2022 as Harvard political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Zoe Marks had called for, we might be better positioned to muster a meaningful opposition.

Instead, we’re caught reacting to the ongoing onslaught of executive orders and oppressive federal actions. So, if a true mass resistance one day manifests, it will only be after we’ve descended even deeper into authoritarianism and oligarchy.

That means underground resistance movements in repressive and authoritarian regimes past and present are the best things we can learn from.

But as we study them, we’d do well to remember that the success of these movements was never inevitable. “In truth,” David McCullough said in an interview for Paris Review, “nothing ever had to happen the way it happened.”

History is full of failed revolutions.

So while Brooks argues that “Americans will eventually reject MAGA,” we must acknowledge that such will only occur if a sufficiently organized opposition articulates a clear alternative, labors to lay the foundation for it, and strives to bring it into being in the face of violent, systemic repression that labels resistors “terrorists” merely for advocating against an economic system that funnels wealth from the many to the few as it poisons the planet and drives us inexorably toward collapse.

I believe that resistance movements past can help us learn how to do all that and more. If nothing else, such a study of history will, as McCullough wrote, inspire “courage and tolerance.”

We’ll need ample reserves of both to withstand the days ahead.

In Closing

To learn how we stand against Trump

We must sit ourselves down on our rumps

And dive really deep

Into history’s keep

To foresee what hurdles we might have to jumpThis piece contains affiliate links for Bookshop.org, a retailer that supports local bookstores. As an affiliate of Bookshop, I earn a small commission when you click through and make a purchase there.