How to spend an evening saving the world

Three hours, twelve people, and an attempt to reach net zero

I had just spent three hours pretending to solve the climate crisis with eleven strangers on a random Thursday night in November when one of them, a software engineer named Nick Kelly, said, “I don’t like that every day I live, I somehow accumulate a more negative carbon balance.”

This comment came in response to the workshop’s aim: exploring what we could do to slash the average carbon footprint of every person in the world down to 2 tons per person per year by 2050 in an effort to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. A French nonprofit developed the aptly named “2tonnes” workshop in 2019. As of October 2023, some 100,000 people have gone through the workshop — which is less seminar than game.

For our particular rendition of 2tonnes, we gathered at 9Zero, a climate innovation hub in Downtown Seattle, with the dozen participants spread around a grey and blue U-shaped modular couch in the common area. Before we dove into the game, Thomas Siffer, a French-born engineer and the evening’s facilitator through his company Terreau, talked through slides covering the basics of climate change and the objective we were after.

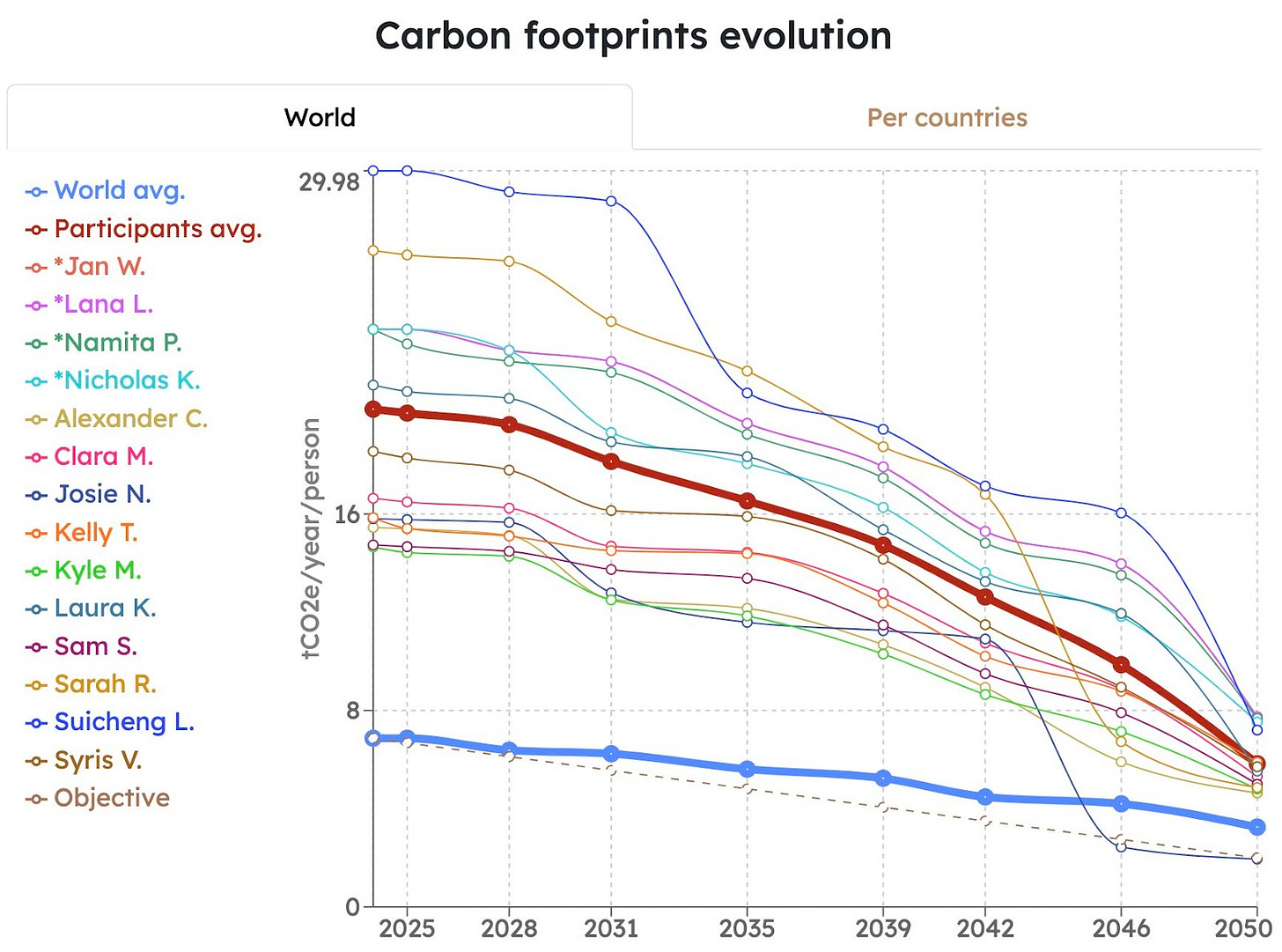

For the remainder of the evening, other than the occasional slide to provide a little additional context, one graph dominated the screen in the center of the room. It showed our individual carbon footprints, their change over time, and the dashed line we were striving to reach.

As we did what we could to fulfill the objective before us, the game sparked a lot of conversations and ample self-reflection. Nonetheless, the game’s core mechanic — the carbon footprint — is also its central conceit.

Though commonplace today, the carbon footprint has been flawed since the fossil fuel industry first popularized it.

As part of an early 2000s rebrand, oil giant British Petroleum (BP) hired ad men from one of the world's most influential marketing firms, Ogilvy and Mather, to publicize a tool that anyone could log on to the BP website and use to calculate their carbon footprint. The campaign aimed to subtly shift blame from corporations onto individual people, environmental policy professor Geoffrey Supran told WBUR last year.

Given how ubiquitous carbon footprints are today, the campaign clearly succeeded, thereby obscuring the public’s ability to understand who's truly at fault for the current crisis.

“We are all complicit to some degree in climate change,” Supran said during his radio spot. “But you and I are passively guilty, stuck in and born into a fossil fuel system. Fossil fuel interests and political ideologues, including BP, on the other hand, are actively guilty, working to stop the system from changing.”

So, by summing the emissions belched by these industries then assigning slivers to each person mulling about a nation, corporations evade blame and avoid any burden to do better. Instead, these footprints pressure individuals to improve their lifestyles for the Earth.

“Fifteen years ago, I took a quiz like this, and that’s what forced me to give up meat,” said design consultant Sarah Rogers during the 2tonnes workshop. “I saw the data and was shocked by the impact that eating meat has on the planet.”

When multiplied by millions, actions like Sarah’s can make an important difference. “But personal action is limited,” Supran said, “because we all live in a society run on fossil fuel power and fossil fuel politics.”

Unless we understand this, these footprints burden us with the shame Nick mentioned without offering us a pathway to make a meaningful difference. Instead, they push us toward symbolic acts of repentance that assuage our guilt without challenging the systems that have made us accomplices in their crimes against people and planet.

2tonnes attempts to free itself from this trap by offering opportunities for participants to explore examples of both individual and collective action, but the limitations of thinking in terms of footprints remain evident.

Across 8 rounds of play, my fellow participants and I watched our simulated footprints tick downward as we each committed to a slate of imagined actions on our own and as a group as we alternated between acting on our own and as a group.

During the individual rounds, we circled around a butcher block table with oversized trading cards spread across it, each representing something we could do to lessen the carbon intensity of our lives: eat less red meat, buy an electric car, install rooftop solar, and so on.

As we passed the cards around the table, we chatted about which ones we already do, which we’d consider, and which (like drinking less coffee) we couldn't fathom. Then we locked in our commitments.

During the collective rounds, half the group roleplayed as a special interest group advocating for an action that they argued the whole world should invest in, like educating girls, preserving nature, funding public transportation, or expanding renewable energy. The rest of the group had to reach consensus on the initiatives to support with our limited funding, and which to leave unaddressed.

At the end of each round, whether individual or collective, we’d face the screen to watch the graph update and see the impact we’d made, in hopes that our carbon footprints would take a big dip downwards.

By stepping between the global change and the minutiae of our daily lives, 2tonnes clarifies that you can’t lighten your footprint alone; it takes a worldwide effort, too. 2tonnes also emphasizes that there is no one-shot solution to the climate crisis; it calls for a cocktail.

“You have to work in all different sectors,” Thomas explained to us. Understanding this can help break the world out of the “triangle of inaction,” he said, where people and businesses and governments point at each saying, “I won’t act until they do.”

But once everyone recognizes that personal choices, business decisions, and policy actions feed off one another (for good and for bad) we can “put ourselves in a virtuous cycle,” Thomas said.

How far that virtuous cycle can take us is, however, limited by the boundaries that existing systems impose on the actions we can take and our ability to imagine what’s possible.

“I’m pretty sure the game is rigged so that you can’t go below two tons,” said Josie Ng, an entrepreneur and product designer who had done a 2tonnes workshop before. (She attended that evening to assist her husband, Thomas.)

If Josie is right and the game is rigged, it’s only because the actions available are purposefully constrained. The creators of 2tonnes don't challenge many, if any, of the assumptions that undergird the politics and economy of our world today. And the actions are largely the run-of-the-mill solutions bandied about the mainstream.

Moreover, the game imagines collective action as something relegated to national interests and not something that communities can push for through labor unions, mutual aid networks, worker-owned cooperatives, participatory democracy, and related efforts. In other words, it’s not a game for radicals who want to reinvent the world. It aims to get the average person thinking about climate action more critically.

Thomas later explained to me over coffee and croissants that 2tonnes allows facilitators like him to introduce people to a variety of complex ideas and concepts in an interactive way, and the game all but ensures that the information sticks. In theory, it can even inspire people to make and push for important changes by showing what they and their governments can do today and in the years ahead — even if 2tonnes’ list of actions is far from comprehensive.

“We are using like 50 cards during the game, 50 little solutions to lower your carbon footprint,” Thomas told me. “But they are not the only ones.” The game’s designers chose these actions over others because, he said, “they are easy to understand.”

That means, for folks like myself, who wish to see more people committed to radically reimagining our world for the better, 2tonnes feels lacking. For instance, even though Thomas introduced the Doughnut Economics framework to help everyone think about what it takes to meet people’s basic needs for food, water, shelter, and healthcare without exceeding our planet’s limits; few if any of the actions seemed to actually nod toward what groups are doing around the world with the support of the Doughnut Economics Action Lab.

And perhaps most disappointing of all, the game seems to undervalue organizing and activism. Participants can certainly opt to campaign, protest, or lobby as one or more of their individual actions. As a former organizer, I did just that. But it made no discernible difference toward the main goal of the game. Yet, movement building is absolutely essential for ensuring that lasting change occurs.

Still, it’s clear that 2tonnes knows what it is and who it serves. So, for someone like me who spends their days dreaming about degrowth and the just transition, it mainly felt like a fun conversation starter. But, for the average person on the street that spends little if any time thinking about climate change, 2tonnes can be a great way to spend an evening thinking about how to save the world.